incense-making in vietnam

making visual and human poetry out of the most ephemeral of items

We’ve all seen them and smelled them - from yoga parlours to out-of-the-way parties to, for those of us who travel, in pretty much every single temple all across Asia. From sticks of varying sizes to month-long-burning circular ones and even small pyramids, each of them smelling something different - jasmine, cinnamon, spices and pretty much everything in-between. Personally I fine myself liking some while others may be a bit too much, but there’s no doubting both the significance they play in buddhist and hindu ceremonies and how important they are for literally billions of people (yes, that’s more than 2 billion!). And hey, photographically speaking, they just look awesome!

Sticks are being fed through the machine until they are smoothed out and in the appropriate dimensions. In the process, all excess material is discarded.

I’m talking, of course, about incense sticks and, believe it or not, more than half of everyone consumed in the world are produced in Vietnam, and more specifically in two areas within Vietnam (the rest are made in China). Contrary to what you may think, almost all of the production within Vietnam comes from small - like, really small - family-owned families. Think about it - more than 20 billion incense sticks (of all kinds) every year come out of the hands - literally - of people like you and me with very little machinery involved but with a lot of backbreaking effort.

For most people, including the users themselves, incense sticks are inconsequential, ephemeral things, tiny consumables destined to be forgotten the moment their ashes blow away in the slightest wind, but to the external observer, to the person coming in from the outside to see how they are made, they become little works of art, each and every one of them, almost magically turned out by insanely dexterous hands in speeds that almost defy imagination. But I’m running ahead of myself - let me start from the beginning.

Incense stick production is, in a very real way, a seasonal production in Vietnam, with production ramping up between the months of November until middle of January as the world prepares for the Buddhist calendar New Year celebrations (Tet in Vietnam, Chinese New Year etc) in the beginning of February. The literally hundreds of small factories, some no more than the members of just one family, will produce, in a little over 2 months, billions upon billions of incense sticks, starting from the selection of the right types of bamboo sticks all the way to the addition of the burning paste and the packaging. Each stick takes between 1 and 2 days from ingredients to the final product and during the high season, entire villages, sometimes including relatives from more distant areas all over Vietnam, will often work 12-15 hours a day doing just this.

The process itself is, surprisingly, a lot more complicated than one may think - certainly a lot more than the respect the final product commands. First there is the burning paste. Each family has its own recipe which is a closely guarded secret - no matter how much I tried, it was impossible to find anyone willing to even consider showing us the mixing process, even if there was no way whatsoever to actually capture and remember what was happening. Raw materials are delivered in their original form - roots, dried flowers etc. - in sacks and inspected by the head of the family before being added to the mix. Even though it starts its life as a dry powder, once oil is added it becomes a very thick paste, not unlike marzipan and is stored in thick clumps covered by an oily cloth. Some of the more well-to-do families have smaller or larger mixing machines but otherwise it is mostly done by hand.

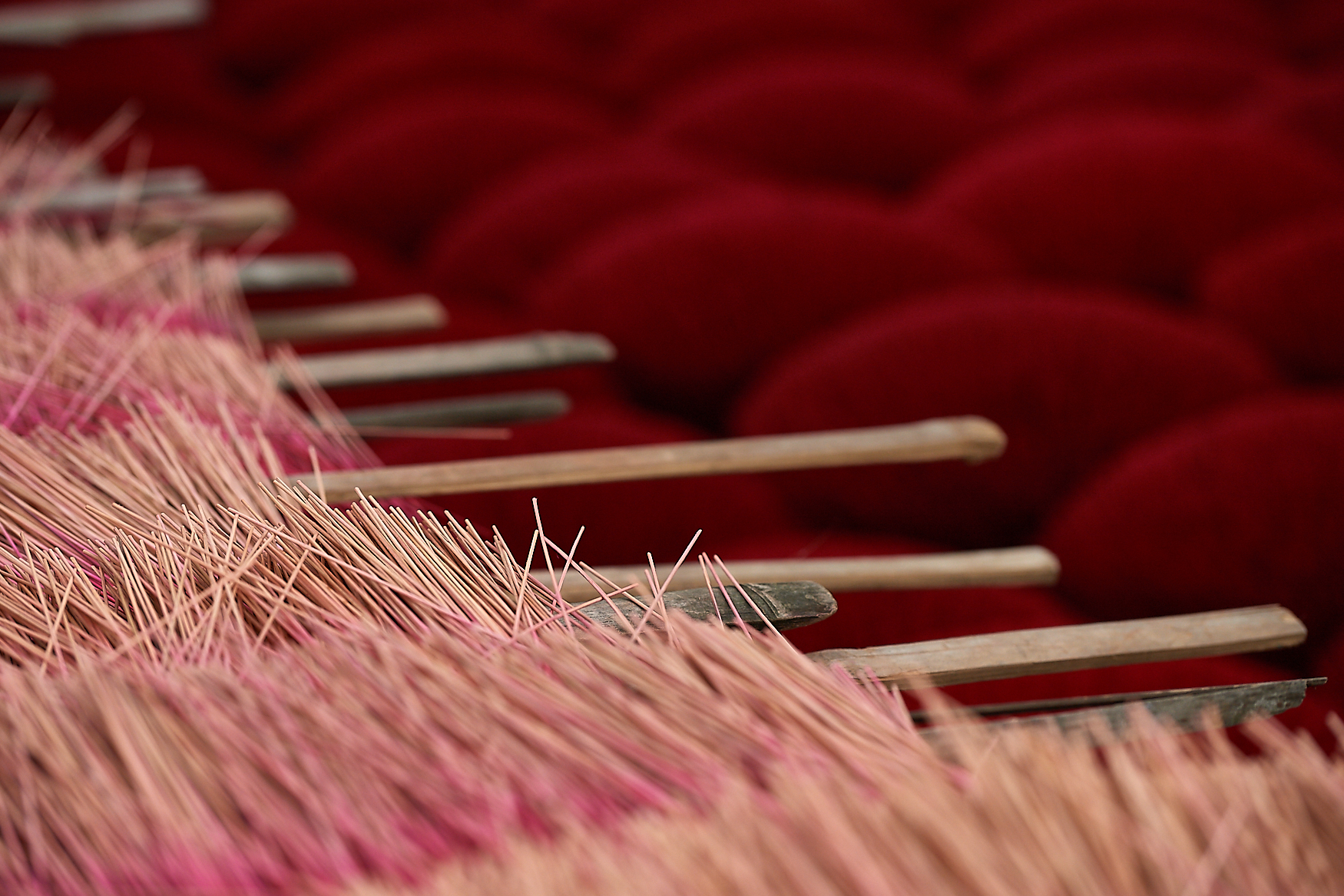

At the same time, at other parts of the village, the bamboo sticks are being prepared. From thick bamboo, first manually and then through a machine, straw sticks start big and slowly, through the process, become thinner and thinner until they resemble the sticks we all know. From all the stages in the production, this is - to my mind - by far the most repetitive and, frankly, wasteful: sticks start at about 2-3cm wide and in pretty much every state of straight. They are then sliced in half, again and again, until they’re about 1cm in width, at which stage they are fed, repeatedly, into a grinding/smoothing machine which sands away imperfections until each becomes a straight and almost identical 2mm round sticks of approximately 40-50cm height. Now, these machines are not intelligent electronic pieces of equipment, constantly monitoring dimensions etc. - they are the absolute basic machines and approximately 5-10 every 100 come out with imperfections or are otherwise not fit for purpose.

The sticks are bundled tightly together and sent for quality control - this is where people, much like you and me, using a very visually beautiful and almost dance-like method, manually remove the unacceptable ones from the lot. Any stick not passing muster is instantly discarded. From all the production stages, this is the more hypnotising to watch as massive bunches are being twirled about until some sticks inevitably fall out - interestingly enough, there is a second level of quality control to catch those which may have escaped the first time, this one even more detailed and usually removes even more sticks than the first pass. The approved sticks are tied together and sent for dyeing.

Sticks are shaken until the weaker and broken ones visibly fall out and are thrown away. This process may be repeated per bunch about 2-3 times until the worker is satisfied there are no more weak sticks.

This is what most people think when they think incenses - the large red, purple or even multicoloured “plumes” of sticks drying in the sun in massive fields! It is a beautiful sight but also a slightly misleading one. You see, I too always thought that the coloured plumes you see are the actual sticks, with their burning paste, but they’re not. Sticks are dyed in bundles by being dipped, repeatedly, into coloured dyes, removed, dried and then redid until the right shade of the desired colour is achieved. What is funny is that the colours we see are the bottom parts of the sticks, the ones not eventually covered by paste and the colour actually serves as a guide for the addition of paste later on in the process! Once sticks are dyed to the desired colour, they are shipped off for the paste to be added.

Now, here’s a funny fact of this part of the process: usually it takes 4 or 5 repeats to get the colour just right and each time the sticks have to be completely dry before they are dyed again. Now, normally, during dry season, this may take a couple of days but during the peak season (which is just after the rainy season) this may take anything between 4 and 5 days. This means that during peak production periods, more and more space is needed to dry the sticks and this results in one of the most beautiful sights in Asia: whole villages where every single open space, including most streets, are literally covered with the colourful “plumes” - when seen from above they look like red rivers flowing among the yellow-coloured houses.

The next stage is the adding of the burning paste. Traditionally, paste was added manually, by women using rolling motions, each time taking a bit more paste and adding it to a stick and so on and so on. These days with demand being what it is, most of this is done by machines which can add paste to 2-3 sticks a second, literally going through thousands over the course of an hour. The machines are quite ingenious in how they work and, to be honest, a lot of fun to watch: they are a really weird mixture of human and machine, with neither part being able to operate without the other: the human pushes one stick after the other through the tiny slot and the machine grabs it, pulls it and in one motion adds the appropriate amount of paste in just the right place. After watching for 30-40’’ you are well and truly hypnotised.

Of course, such a combinational process does come at a price: 5-10 sticks out of 100 end up either incomplete or with more paste than required and are immediately discarded - there is no recycling here. Once a bunch has been prepared, they are laid out to dry (usually for no more than 1/2 day) before being packaged and prepared for shipping to the stores. To be honest, I always thought that there would be different production cycles for different markets, needs etc., but this does not always appear to be the case: from the same batches different packaging is being prepared - I can only imagine what the differences are (the people I witnessed doing this could not explain the difference).

There is one exception to the above: the long-burning circular ones - those take longer but are even more magical to see. As there are no machines capable of automatically putting paste in perfect circles, these are all done manually. A machine takes the paste and compresses it, shooting it out in 2-3mm thick strings, some more than 10-20m. These are then taken by men (usually) who, using simple templates on a plain wooden board and nothing but their dexterity and fingers, create concentric circles in the rate of 1 every 4-5’’ (yes, that’s seconds). Once a board is filled, it is taken to dry in the sun. The dance of the paste strings as it literally flies through their fingers is magical - like an etherial dance manipulated invisibly by calloused fingers.

I cannot write enough about how beautiful the whole process is from start to finish - yes, it’s filled with (saw)dust (your camera will be absolutely covered in it both during the sanding as well as in the paste-mixing stages) and yes, it does involve a lot of standing under the burning sun following the women who lay out, either the finished sticks or the base ones, to dry (even though, visually, this is by far the most rewarding!), but what makes it, for me, beautiful is the people - working in what is, quite likely, not the best of conditions, they always talk to each other, always laughing (mostly at you, the hapless observer, but still) and always happy to share a joke (again, quite likely at your expense) and tease each other. In all my time among them I don’t think I came across one of them who was either angry or negatively disposed to the observer. This is, I believe, the 4th or 5th such experience I’ve had only recently where the nicest, most communal and happiest working environments are often found in the most unlikely of places - makes one wonder, no?

And now, as always, the photography-related advice:

technically speaking, nothing is easier than photographing the incense villages of northern Vietnam. Light is ample, even inside the warehouses and the factories and, with the exception of some of the stages of the process, it is not demanding either in terms of focus or speeds.

finding areas where sticks are being set out to dry is a little more complicated and the average photographer may be discouraged upon arriving at a village. You need to walk around - possibly a lot - go into countless side streets and look into every yard and enclosed space until you find areas where they are laid out. Be patient and insistent. Look for places where they may JUST be starting to put them out or even areas where they are dyeing them - sometimes it’s just as simple to follow a cart filled with dyed sticks to its destination.

do not count, under any circumstances, in changing lenses anywhere in and around the village! The tiny particles of bamboo and incense dust are literally everywhere - and this is not dust. These are thick, damaging particles of dust which, once inside your camera WILL do damage. If you have one body, choose a medium zoom lens (a 24-70?) and stick with it - but I would recommend two bodies.

But above all, please, please, speak to people - they are doing usually hard and mundane work and they’re allowing you into their lives. Smile, show them their pictures, thank them, buy them a bottle of water if you don’t see one near them. Give us photographers a good name, show us to be humans. I saw groups of oriental (maybe Chinese? maybe Taiwanese?) tourists on “photo tours” pushing people around, forcing them into “positions” they felt were more photogenic, shouting at them to stop so they could get an image they wanted and then, when done, leaving (after the obligatory group selfie of course) without a single acknowledgement, a single wave! Don’t be those people - be better!